3 — Indigenous Australians

13 February 2008 🙂

Read: Kevin Rudd’s Apology — full speech PDF; Dr Nelson’s speech in reply PDF

See also the new Indigenous Australia page on New Lines from a Floating Life.

In February 2008 the long awaited Apology went before the Australian Parliament.

— This site is mainly for Years 11 and 12 and interested members of the general public. To evaluate links from a teaching perspective, though, follow this rough guide:

This site is mainly for Years 11 and 12 and interested members of the general public. To evaluate links from a teaching perspective, though, follow this rough guide:

suitable for everyone.

suitable for everyone. mainly for Years 7-9.

mainly for Years 7-9. Years 10-12, teachers, and adult readers.

Years 10-12, teachers, and adult readers.

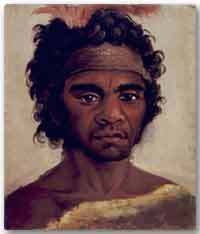

The picture on the right dates from Governor Macquarie’s time and is a rare example of a sympathetic portrait of a Sydney Aboriginal man of the early 19th century.

The core of this page was created in 1997-1998 as material to support HSC English study of  Wild Cat Falling*. It was modified and added to 12-15 August 2005 to support a Year 11 unit at Sydney Boys High. Now it is time for a thorough revision. A lot of water has gone under the bridge since the core of this site was created in the late 90s. I refer you to

Wild Cat Falling*. It was modified and added to 12-15 August 2005 to support a Year 11 unit at Sydney Boys High. Now it is time for a thorough revision. A lot of water has gone under the bridge since the core of this site was created in the late 90s. I refer you to  Bain Attwood, Telling the Truth About Aboriginal History, Allen & Unwin 2005 and as starting points for further study, go to Wikipedia on

Bain Attwood, Telling the Truth About Aboriginal History, Allen & Unwin 2005 and as starting points for further study, go to Wikipedia on  The History Wars and my blog entry

The History Wars and my blog entry  Stuart Macintyre and Anna Clark, The History Wars. But I will tell you something for free: few better things have been said about Indigenous Australians than

Stuart Macintyre and Anna Clark, The History Wars. But I will tell you something for free: few better things have been said about Indigenous Australians than  Paul Keating’s Redfern Speech of 1992.

Paul Keating’s Redfern Speech of 1992.

We non-Aboriginal Australians should perhaps remind ourselves that Australia once reached out for us. Didn’t Australia provide opportunity and care for the dispossessed Irish? The poor of Britain? The refugees from war and famine and persecution in the countries of Europe and Asia? Isn’t it reasonable to say that if we can build a prosperous and remarkably harmonious multicultural society in Australia, surely we can find just solutions to the problems which beset the first Australians – the people to whom the most injustice has been done.And, as I say, the starting point might be to recognise that the problem starts with us non-Aboriginal Australians.It begins, I think, with the act of recognition. Recognition that it was we who did the dispossessing. We took the traditional lands and smashed the traditional way of life. We brought the diseases. The alcohol. We committed the murders. We took the children from their mothers. We practised discrimination and exclusion.

It was our ignorance and our prejudice. And our failure to imagine these things being done to us. With some noble exceptions, we failed to make the most basic human response and enter into their hearts and minds. We failed to ask – how would I feel if this were done to me?

See also 7th Vincent Lingiari Memorial Lecture: Linda Burney MP.

See also 7th Vincent Lingiari Memorial Lecture: Linda Burney MP.

Let me declare myself. Although on my father’s mother’s side I may be descended from the  Dharawal people, I do not claim aboriginality. You may read about my ancestry on

Dharawal people, I do not claim aboriginality. You may read about my ancestry on  About the Whitfields. My nephew is legally Aboriginal, his mother also being of Aboriginal descent from the family of

About the Whitfields. My nephew is legally Aboriginal, his mother also being of Aboriginal descent from the family of  Bungaree, who sailed with Matthew Flinders. My nephew tells this story

Bungaree, who sailed with Matthew Flinders. My nephew tells this story  here.

here.

Emerging from the Great Australian Silence

Through my school years in the 1950s and my training as an English and History teacher in the 1960s the main characteristic of Australian thought on the subject of Aboriginals was embarrassed (guilty?) silence. In Sydney one hardly ever saw an Aboriginal person, unless one went on a Sunday excursion to the suburb of La Perouse where the descendants of some Eora but mainly Dharawal and Dharug people still lived. Unknown to us, of course, there were many other descendants of the first Australians among us, like my nephew’s mother’s Guringai family, still on their ancestral land to the north of Sydney. Like many, I wondered where the Aboriginal people had gone, but the nearest we ever got to an answer was to read Henry Kendall’s 19th century poem “The Last of his Tribe”.

He crouches, and buries his face on his knees,

And hides in the dark of his hair;

For he cannot look up at the storm-smitten trees,

Or think of the loneliness there –

Of the loss and the loneliness there.The wallaroos grope through the tufts of the grass,

And turn to their coverts for fear;

But he sits in the ashes and lets them pass

Where the boomerang sleeps with the spear –

With the nullah, the sling and the spear.

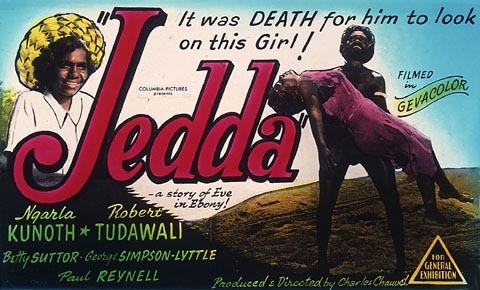

We used to marvel at the rock carvings at  Bundeena, south of Cronulla. The experience of my country cousins was of course different. Aboriginal people, the Wiradjuri, were inescapable around Dubbo and Wellington. And there were other presences too, even in the city. I can recall at age twelve being quite disturbed by the 1955 movie

Bundeena, south of Cronulla. The experience of my country cousins was of course different. Aboriginal people, the Wiradjuri, were inescapable around Dubbo and Wellington. And there were other presences too, even in the city. I can recall at age twelve being quite disturbed by the 1955 movie  Jedda.

Jedda.

It is easy for an older Australian like me to be torn and ambivalent about Aboriginal issues. On the one hand, as this page attests, I support the “black armband” view of Australian history, not as infallible but as at least being prepared to recognise the uncomfortable facts about our history; the revisionists too often define away the only possible sources of information about the Aboriginal past by a pedantic adherence to written documents which are, of course, overwhelmingly victor’s history, or quite clearly whitewashes. So one supports reconciliation; one may have even experienced, just a little in my case, the thrill of contact with some authentic Aboriginal culture now and again, such as being privileged in 1988 at a party at my friend  Kristina Nehm’s home to hear a dreamtime story from a genuine songman, in Sydney for the Bicentennial. On the other hand, one can easily despair at the apparent hopelessness one also sees, and some still are uncomfortable with Aboriginal issues on a spectrum ranging from racism at one end through genuine distress over the apparent slow progress at the other.

Kristina Nehm’s home to hear a dreamtime story from a genuine songman, in Sydney for the Bicentennial. On the other hand, one can easily despair at the apparent hopelessness one also sees, and some still are uncomfortable with Aboriginal issues on a spectrum ranging from racism at one end through genuine distress over the apparent slow progress at the other.  Jim Belshaw has some interesting and honest reflections on this.

Jim Belshaw has some interesting and honest reflections on this.

Issues in this area are not simple by any means. Reconciliation, however, depends on all Australians, whatever their background, knowing and acknowledging our shared history — whether it is a source of pride (as much is on both sides) or a source of shame. It’s not about guilt, it’s about honesty! In his Black Sheep: Journey to Borroloola (London, Profile Books 2002),  Nicholas Jose has this to say:

Nicholas Jose has this to say:

I got into trouble once for writing that Aboriginal issues were therapy issues for non-indigenous Australians. I was thought to be trivialising matters when, on the contrary, I meant to imply that the issues live inside all of us, inseparable from us. That is why we bristle when we are told to shut up and listen for a change.I think Jose will one day be recognised for saying some very original and insightful things about the uneasy identity of 21st century Australians, not to mention about language and civilisation. I’ll confess to being a bit of a fan, but I really do think this book has not had the recognition it merits. There is an extensive review in Black Sheep of

Plains of Promise by Aboriginal writer Alexis Wright (UQP 1997); it sounds marvellous.

Further, one needs to remember the many positive stories, the Aboriginal successes. See the ABC-TV program  Message Stick. Also go to the

Message Stick. Also go to the  National Indigenous Times, “Australia’s leading Indigenous Affairs news provider.”

National Indigenous Times, “Australia’s leading Indigenous Affairs news provider.”

Some historical issues to consider.

Sydney in the 1820s

FACT: The last “official” massacre of Aboriginal people occurred at Coniston Station in the Northern Territory in 1928. Just how many Aborigines were killed in the years since the invasion, and whether or not there was a  “stolen generation” (the subject of a now — for some — controversial report linked there), have recently become subject to revisonist and/or reactionary arguments. Quite a few commentators and journalists, have mounted the most sustained attacks in reaction to that bete noir of the reactionary, “political correctness”. It is true that leftist pop gurus like John Pilger have often been careless with their facts. What needs to be kept in mind, however, is that thanks to serious historians like Henry Reynolds, we now have a much better sense of Australia’s true history — a history I never learned in school.

“stolen generation” (the subject of a now — for some — controversial report linked there), have recently become subject to revisonist and/or reactionary arguments. Quite a few commentators and journalists, have mounted the most sustained attacks in reaction to that bete noir of the reactionary, “political correctness”. It is true that leftist pop gurus like John Pilger have often been careless with their facts. What needs to be kept in mind, however, is that thanks to serious historians like Henry Reynolds, we now have a much better sense of Australia’s true history — a history I never learned in school.

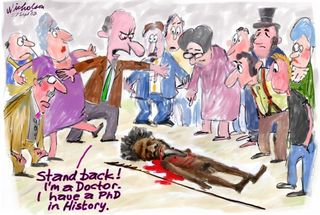

“History Wars” — cartoon by Nicholson.

The Sun-Herald (April 9 2000) offered this summary history for my own State, NSW:

- 1890: The Aborigines Protection Board develops a policy to remove children of mixed descent from their families to be “merged” into the non-indigenous population.

- 1893-1909: About 300 Aboriginal girls are placed at the Earangesda station dormitory in south-western NSW.

- 1914: The board tells station managers that all mixed-descent boys aged 14 and older must leave stations and find employment, and all girls 14 and older must go into service or to the Cootamundra Training Home for girls.

- 1915: Aborigines Protection Amendment Act gives the board total power to separate children from their families without having to establish in court that the girl or boy was neglected.

- 1921: By this year, 81 per cent of children removed are female.

- 1920s: Between 300 and 400 Aboriginal girls are apprenticed to white homes each year.

- 1925: The Australian Aborigines Progressive Association in NSW calls for an end to the forcible removal of children from their families.

- 1940: The Protection Board becomes the Aborigines Welfare Board and is given powers to establish homes for the training of Aboriginal wards. Children leaving their “home” or employment are punishable by the Children’s Court.

- 1940s-1950s: Lighter-skinned children are sent to institutions for non-indigenous children or placed in foster care with non-indigenous families.

- 1960: Over 300 Aboriginal children in NSW are in foster homes, and about another 70 are at Cootamundra or the Kinchela Training Institution, a boys’ home [where the father of Aboriginal former

Senator Aden Ridgeway grew up].

Senator Aden Ridgeway grew up].

- 1969: The NSW Aborigines Welfare Board is abolished, leaving “over a thousand” children in institutional or family care.

Similar issues are raised in the film  The Rabbit-Proof Fence about Western Australia, parts of which, along with much of the Northern Territory and parts of Queensland, really only saw white settlement (or attempted settlement) within some people’s living memories, or those of their parents and grandparents. Do read Doris Pilkington (Nugi Garamara), Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence, University of Queensland Press, 2000, as the film, while excellent, does take some liberties for dramatic reasons.

The Rabbit-Proof Fence about Western Australia, parts of which, along with much of the Northern Territory and parts of Queensland, really only saw white settlement (or attempted settlement) within some people’s living memories, or those of their parents and grandparents. Do read Doris Pilkington (Nugi Garamara), Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence, University of Queensland Press, 2000, as the film, while excellent, does take some liberties for dramatic reasons.

In Quadrant in 1997 Robert Manne wrote an editorial on the background to stories like these. That editorial eventually led to his being sacked. Manne took up these issues at length in many books and essays. See  The Stolen Generations: Robert Manne’s essay. The whole issue continues to be controversial. See

The Stolen Generations: Robert Manne’s essay. The whole issue continues to be controversial. See  Wikipedia.

Wikipedia.

THE AGE OF BIOLOGICAL ASSIMILATION

I cannot remember another occasion when a few minutes of television shocked me so deeply. I was watching the last minutes of the final episode of the ABC series Frontier. The program, which concerned the relations between Aborigines and Europeans in Australia, had reached the 1930s. It revealed how a number of the most powerful figures in Aboriginal affairs had arrived at what they thought of as a long-term plan for the solution to the Aboriginal problem.

Such men were convinced that the “full-blood” tribal Aborigine was destined, no matter what policy Europeans might adopt, to die out. Their thinking focused on the future of the “half-caste”, whose number was growing alarmingly. They believed in a policy of biological assimilation, that is to say that the solution to the problem of the half-caste was a policy of breeding out. The prospects for a solution such as this were excellent. Dr Cook, the Protector in the Northern Territory, believed that within six generations of mating between natives and Europeans every trace of Aboriginal blood could be removed. The program quoted a sentence from a speech A.O. Neville, the Commissioner of Native Affairs in Western Australia, made to the first national conference of Aboriginal administrators, held in Canberra in April 1937: “Fifty years hence … are we going to have a population of one million blacks in the Commonwealth, or are we going to merge them into our white community and eventually forget that there were any Aborigines in Australia?’

These words had for me a very particular meaning. As a student, almost thirty years ago, I read a book on the Nazi campaign of Jewish mass extermination, Hannah Arendt’s “Eichmann in Jerusalem”. In its closing pages it revealed something which I had not previously understood. Arendt was trying to explain the precise nature of the crime committed by the Nazis against the Jews. Her explanation went thus: “It was when the Nazi regime declared that the German people not only were unwilling to have any Jews in Germany but wished to make the entire people disappear off the face of the earth that the new crime, the crime against humanity–in the sense of the crime against the human status–appeared.” Arendt called the German crime “an attack upon human diversity”. It was this diversity which gave meaning to ideas like “mankind” or “humanity”. At the heart of the crime the Nazis committed was their belief that they had the “right to determine who should and who should not inhabit the world”.

When we use the word genocide we tend to think first of the Holocaust. Because of this, two rather different ideas–mass murder on a vast scale and the intention to eliminate a distinct people–are collapsed into one. Yet it seems to me that the idea of the Holocaust as our model for genocide may be misleading. There can be vast acts of state-inspired mass murder — for example Stalin’s crimes–which do not amount to genocide. There can be deliberate policies of a state, which aim at the elimination of a people, which do not involve even one killing. If the final five minutes of Frontier gave an accurate account of what some of the most important administrators in Aboriginal affairs in the late 1930s were anticipating and planning–to allow the full-blood Aborigines to die out, and to breed out the half-castes–then it seemed to me inescapable that in at least one period in our history something genuinely terrible — genocide in the Arendtian sense–had been seriously contemplated by those who held in their hands the powers vested in them by the state, to administer Aboriginal affairs.

Since those five minutes of Frontier I have begun to read about this period of Aboriginal administration. I turned first to the report on the stolen children, Bringing Them Home. I have written about it in a previous Quadrant. It records in unrelenting and piteous detail the stories of the mental and physical suffering of the infants who, as part of the assimilation policy, were taken from their mothers and placed in institutions. Clearly, human suffering of this kind was beyond the imagination of those who pioneered the policy. The natives were not “like us”. To discover how the ex-administrators thought, I turned next to the verbatim report of the Canberra conference of 1937. Neville emerged here as the dominant figure, the most systematic planner. He revealed to his colleagues his scheme for the absorption, by means of biological assimilation, of the Aboriginal population of Australia. Neville had acquired the legal power to control the lives of all the “natives” under his care, until they reached the age of twenty-one. Under the state’s laws he had moulded, it was more or less illegal for half-castes to marry full-blood Aborigines. Even marriages between half-castes were discouraged.

In order to prepare them for their absorption into European society, in his view all half-caste children should be taken from their mothers and institutionalised before the age of six. The prospects for absorption were good. Aborigines were, he argued, of remote Caucasian link. The likelihood of biological “throwback” was slim.

In recent times, in response to the stolen children report, many conservatives have spoken of the policies of the previous generations of Aboriginal administrators as ill-advised but well-intentioned. Neville’s book is, in fact, full of precisely such good intentions. Neville writes, as he puts it, “on behalf of” the natives. He chastises his fellow Australians for their indifference; their racial prejudices, including their prejudice against miscegenation; their unwillingness to spend money to fund his absorption plan.

And yet nothing could more expose the barrenness of the “good intentions” defence than this terrible book. In it Neville advocates the taking of all non-tribal Aboriginal children from their parents. He speaks fondly of those imagined natives willing to live their lives according to his absorption plans. But for those benighted enough to resist him he has nothing but profound contempt.

Conservatives rightly mock to scorn those who defend Lenin on the ground of his good intentions. They defend family values. Yet some now tell us that at least the intentions of those who seized babies from their mothers in the hope of building a future where Aboriginal people would no longer share the world with them were good.

It should be noted that at the conference in 1937 Neville’s views on the ‘breeding out’ of ‘half-castes’ were rejected by Queensland and all the southern states. (Rosalind Kidd, The Way We Civilise, UQP, 1997, p. 141.) However, the Queensland objection was that only ‘low whites’ would enter into marriage with half-castes. It is worth noting that the pre-War Queensland laws were used as a model by the South African government under apartheid.

Two Stories: Ernie Dingo and Wayne King

I transcribed a number of extracts for my class in 1997. These two are still of interest. Ernie Dingo: Australian television personality — from Sally Dingo, Dingo, Sydney, Random House, 1997, pp. 283-289.

Ernie Dingo: Australian television personality — from Sally Dingo, Dingo, Sydney, Random House, 1997, pp. 283-289.

Back in Sydney [in the early 1990s] Ernie resumed his larger-than-life personality, all confidence, smiles, and the funny lines he was so good at, spreading the illusion the world was at his feet… On his own, though, he and I both knew the truth. I’d seen the shopkeepers keep him waiting until last, pretending he wasn’t there, serving anyone but him. I’d seen the look on his face. I’d seen his helplessness as he stood on the footpath outside real estate offices, sending me in to ask the questions, to get the keys, to do all the talking. We found places to rent this way, but once, even with the lease signed, when we returned to look over the house, the owner who lived next door came running–and suddenly the house needed immediate repairs, was no longer available, not to us anyway.And on a well-earned holiday at a resort in Broome, a package trip we had saved for, Ernie was ordered from the pool, shouted at to get out, the manager refusing to believe he was a paying guest. Ernie, still in the water, looked up at the towering figure above, nervously stumbled over his words and forgot our room number, the manager gleeful that he had indeed been right. This Aboriginal person in their swimming pool was lying! It was only when Ernie managed to hoist himself out of the pool, search in all his pockets, the manager standing smug in his certainty, that on producing the key he received an explanation, but not an apology. There’d been someone in the pool who shouldn’t have been, so he’d been told. And he’d come straight to Ernie, presumed guilty because of his race. I watched from a distance, horrified, wondering what to do, having made a recent decision that I shouldn’t do it all for Ernie in my world, that he must learn to stand on his own. Many guests, some high profile, watched with their mouths wide open.

And once I was shamed by my own actions, after a disagreement, our first few years of marriage littered with such arguments while we both learnt how to be married. I refused on that one occasion to enact the technique most couples of our racial mix use to hail a cab. I refused to take my place on the street and attract their attention, sending Ernie instead. He vainly tried taxi after taxi, looking back at me pleading, pain on his face. With tears brimming in his eyes, he asked me again, and I stepped forward, the very next cab pulling to the curb. He ran and got in. I felt sick at how I had baldly, callously, laid before him the position he was allotted in our society. He knew it already. It was one of the reasons he tried so hard every day…

After describing a hard time over their inability to have a baby, Sally Dingo goes on:

Ernie and I were shell-shocked by it all, turned away from each other, had a lot to work through if we wanted to stay together. And Ernie had the additional problem of increasing fame with more television appearances, of people wanting to know him, telling him he was invincible, telling he was something other than himself. For a time the fringe-dweller boy who grew up in a humpy, the boy who’d been called nigger, became ensnared by the fantasies fame peddles, beguiled by how well he’d been accepted, his innocence preventing him seeing the dangers which could arise. We were at crisis point.

‘Slow down,’ Bessie [his mother] ever wise told him.

‘Decide,’ I said.

And Ernie chose family, had always thought family, but presumed one would always be waiting.

We’d come a long way, different people from the two who fronted up at the Registry Office in 1989. We could now move on. And Ernie, the bloke, decent and lovable, the mate who genuinely enjoyed people wherever he went, had his feet firmly on the ground again. It was good to have him back.

These things still happen in 2006. Ask any Aboriginal person. There are people of my acquaintance who have experienced such things very recently.

Wayne King, Black Hours Sydney, A & R, 1996, pp. 39-43 and pp. 154-166.

Wayne King, Black Hours Sydney, A & R, 1996, pp. 39-43 and pp. 154-166.

My dislike of school grew when we were introduced to Australian history. We were told of how the exploits of the great British explorers were often impeded by the local Aborigines who were ‘barbarous savages’. I was the only Aborigine in my class, and it cut to the quick. With my olive skin, dark hair and black eyes, I stood out in that classroom. Were my fellow students looking at me with disdain for the impediment my people placed in the way of ‘civilisation’? Probably not, but I felt they were. And did the teacher spit out the words ‘barbarous savages’ invectively? I thought so. Alternatively, he spoke proudly of the mighty explorers who were the first men to discover Ayers Rock, the Murray River or the Blue Mountains. Not the first ‘white men’ but the ‘first men’. There was no way out, either: to pass the history examination at the end of the year you had to learn it.And there was no way out of high school either. Mum dug her heels in. Later I found out why she had been so insistent. She had wanted to go to high school but had not been allowed because of Queensland’s apartheid laws, which prevented Aborigines from attending high school. She had made up her mind that her children were not going to be denied the chance…

The two years passed and I was glad to leave school. Aborigines were always told that education was the key which would unlock the door to mainstream society. But I knew better. At sixteen [1964] I knew that education wouldn’t enable Aborigines to take their place in Australian society. Aborigines could’ve had PhDs and shat roses and it wouldn’t have mattered in Australia.

A cousin of mine had done what, in those days, was called Senior–four years of high school. After leaving high school, he got a job with the Commonwealth Bank. After a year in the bank, he was offered a transfer to a branch office in Rockhampton, two hundred miles away on the north coast of Queensland. It was the bank’s policy when transferring staff to find them accommodation. Several weeks passed and there was no mention of his transfer. Nearly two months passed before he decided to approach the manager, who explained that they were having difficulty finding him accommodation. When people who had replied to the bank’s enquiries found out he was Aboriginal, they withdrew their offer of accommodation…

* * *

I returned to Sydney [from a time in New York working for the United Nations] to find a job and to try to get myself settled.

Australia was experiencing a recession. The influx of Asian migrants hadn’t abated, and in the current economic climate the Anglos resented them even more. It wasn’t racism, of course; it was the same old excuse–they took jobs away from Australians. The lack of progress of the human spirit saddened me. Show Anglos a jigsaw where the pieces were all the same size and colour and they would accept it.

The media referred to non-Anglos as ‘the man, a Vietnamese’, or a Turk, Czech or Lebanese. Maybe it was indeed my sensitivity gone mad; perhaps ‘the man, a Vietnamese’ had come rushing out to the journalist waving a foreign passport and citizenship papers.

The concept of multiculturalism had been developed. It was supposed to teach people to understand, tolerate and revel in the differences between different groups. But Aborigines didn’t fit in to multiculturalism. Australia was now divided into Australians, ‘ethnics’, and Aborigines.

I got a job with the ABC as a casual telex operator and found a flat in Randwick. As I worked the morning shift, I wanted to get a job for the afternoon hours. But jobs were hard to find, something I had never experienced before. I went to an employment agency. They were surprised to see a male applying for a job and I had to convince them that not only could I type but that I was fast. Also, in New York I had learned word processing. They were able to convince a well-known chartered accounting firm to employ me.

Some nights I took taxis home from work. The drivers, intrigued by my slight American accent, were curious to find out if I was American and, if so, what I thought of Australia. Discovering that I was Australian they then quizzed me about my ethnic origins. When I told them I was Aboriginal, they became confused. They didn’t believe me, saying I had to admit I didn’t look Aboriginal. Had to admit that I didn’t look Aboriginal? For whom? Where was Alfredo with his ‘don’t take it personally’? Here I was having to explain my existence.

Everywhere, people wanted to know how, as an Aborigine, I was entitled to their land. Trying to explain that land rights in Sydney suburbs weren’t the issue was useless. Also, they said, taxpayers’ money was being poured into Aboriginal affairs like water and it shouldn’t be handed out so freely. It was pointless to tell them that, like many Aborigines, I paid taxes; that my father had paid taxes for nearly thirty years without being a citizen. Huge sums of money were indeed being poured into Aboriginal affairs but it was impossible to explain that it was to redress almost two hundred years of neglect of Aboriginal health, welfare and education. People refused to hear me out.

One night a taxi driver launched into an anti-Asian tirade. He finished his drivel with the statement that in order to migrate to Australia a white man had to be a millionaire and have a PhD. Sick of listening and wanting to put an end to his offensive words, I replied that if what he said was true, it was a turn-around; historically, white men had only to have a criminal record to come to Australia. The remainder of the ride home was blessed with silence.

I was fighting for my rights and fighting to belong. Then my job with the accounting firm finished and the agency couldn’t find me another one. I was devastated. The nightmare had stopped, but not the drinking. Nor the voice in my head, which never gave up berating me and making me feel small. Without an income I was suddenly very afraid. In desperation I rang the ABC on the off-chance of even the odd day’s work. If I wasn’t taking care of myself then somebody was: a staff member had just resigned and I was told if I wanted the position, it was mine. I was so grateful.

In late 1981 I was invited to a dinner party by one of the women from the office. There were eight of us and we discussed generalities over drinks and soft background music. Eventually the conversation turned to New York…

During all this time I noticed that one of the male guests was staring at me. It was a stare I recognised; it meant I was back to having to explain who I was. He waited for a lull in the conversation, then turned to me and said that he didn’t believe I was Aboriginal. Was I really Aboriginal? In 1981, in a middle class suburb of Sydney, I was back to square one… Next came the typical 1981 Australian justification for not facing the racism against Aborigines–the existence of the ‘ethnic community’. He said that the ethnic communities could build successful lives for themselves in Australia. If the ethnic communities could…rise above what I called the racism, then there must be something wrong with the Aboriginal community.

I was angry. As Barbara would say, I was getting sick of trying to educate white people. However, out of respect for my hostess, I bit my tongue, took two deep breaths, and tried to remain calm. I said that in any institution there was a hierarchy. In the institution of racism in Australia, Aborigines were on the bottom of the ladder. Further, I said, there was no comparison between the ethnic communities and the Aboriginal community. Migrants chose to give up their countries. Such a choice wasn’t available to Aborigines; our country had been taken from us. Migrants had come to Australia with their culture intact; they had at least their self-respect to hold on to. If Aboriginal culture had survived, it was only because Aborigines had occupied land that was, in the European sense, deemed useless at the time. Not only was the traditional life of Aborigines destroyed, but the lives of entire peoples and of countless families. Aboriginal children had been taken hundreds of miles from their families, never to know who they were or where they belonged, often never to see their families again. The destruction of the family is a memory which lives on in the Aboriginal community.

[Including Wayne King’s own mother, as Chapter 22 most movingly describes.]

I continued to be confronted by ignorance and racism, and not just by strangers at dinner parties. ‘What do you call an Aborigine behind the wheel of a brand new car? A thief.’ This so-called joke was told to me by a friend, a girl I worked with. One day she came to me and said she had a joke, an Aboriginal joke; did I want to hear it? I said that I didn’t, explaining that I found Aboriginal ‘jokes’ offensive. But she went ahead anyway, because it was ‘funny’, and we had to be able to laugh at ourselves. I wanted to slap her in the mouth. I was so angry, I imagined strangling her, holding her by the throat with my hands and squeezing, slowly. I imagined playing God and telling her she was unfit to live. I wanted her to know the sadness, the disappointment, the hurt of betrayal.

Yet I knew she liked me: we helped each other out with work, lunched together, had long talks, joked and partied together. If she liked me yet could still treat me in this way, did that mean I couldn’t trust any of them? It was life on the razor’s edge–be friendly but cautious, they could turn at any time.

The racism was a burning pain that only alcohol and drugs kept in check. There were times when, without them, I knew I was a walking time bomb. Whoever says that booze and drugs are evil, spit in their eye. Except in my imagination, they’ve prevented me from killing many times. In spite of the volcano that was churning in the pit of my stomach, I remained as cool as a cucumber. I told the girl with her stupid joke that I was in Australia because my people had been here for more than forty thousand years. She, on the other hand, was here because her forbears were convicts. As such, the really funny part of the joke was her referring to Aborigines as thieves.

The office had gone so quiet you could hear a pin drop on its carpeted floor. She sheepishly crept away to her office and two minutes later called me in, saying she was sorry. She said that she didn’t think of me as Aboriginal.

When I got home that night, I closed the door, drew the blinds, took half a tab of acid and opened the vodka. Half an hour later, when the drugs kicked in, I was happy. I could even forgive her in that state of synthetic well-being. I knew she liked me. Yet if she who liked me could make such a blunder, what about the people who didn’t? Was there any hope? But it was pointless wasting good drugs on such ponderous questions. Drugs were for good times.

***

Slowly I was slipping further and further towards dereliction, with drugs and booze greasing my slide. I couldn’t seem top get a firm grasp on my life. All that time I’d spent with Alfredo in Cairo, watching people’s behaviour to see what they would unwittingly tell me about themselves, had not helped me to examine my own life. Something was very wrong. I had to find out what it was.

I had come to accept that I was intelligent–not like Trevor, Chris or Stephen, but I wasn’t stupid. I had even been handsome, but now my face was showing the signs of alcohol and drug abuse. Also I was getting older. Soon my health would go and then I really would be up shit creek. I had to find out what had gone wrong and where; why I had squandered my youth, looks and intelligence and achieved so little. A philosopher once said that sometimes the fastest way forward is to go back. I didn’t have anything to lose by doing this. Given what I knew about the apartheid that not only my grandparents but my parents had grown up under, it seemed the place to start, so I went back to Ipswich.

Further reading

Further reading

Maybe Tomorrow by Monty Boori Prior, whom I have met on several occasions. He is a very positive character indeed and practises what reconciliation should be about: sharing.

Maybe Tomorrow by Monty Boori Prior, whom I have met on several occasions. He is a very positive character indeed and practises what reconciliation should be about: sharing.

Indigenous Issues In Australia from the Australian Politics site brings together many significant documents and speeches.

Indigenous Issues In Australia from the Australian Politics site brings together many significant documents and speeches.

Australian Indigenous People from the P.L. Duffy Resource Centre, Trinity College, Western Australia.

Australian Indigenous People from the P.L. Duffy Resource Centre, Trinity College, Western Australia.

Lore of the Land. “Lore of the Land is designed to encourage us to live in harmony with each other and with the land we each call home. Through deepening our knowledge of who we are and where we are together, we can create a new story.”

Lore of the Land. “Lore of the Land is designed to encourage us to live in harmony with each other and with the land we each call home. Through deepening our knowledge of who we are and where we are together, we can create a new story.”

Living Black: Australian Indigenous current affairs program on SBS.

Living Black: Australian Indigenous current affairs program on SBS.

Message Stick: Australian Indigenous current affairs program on ABC. Also leads to important radio sites.

Message Stick: Australian Indigenous current affairs program on ABC. Also leads to important radio sites.

Barani: “Barani is an Aboriginal word of the Eora, the original inhabitants of the place where Sydney City now stands. It means ‘yesterday’. Sydney dates from the arrival of the first convicts to the place in 1788. For Indigenous people, who have lived here for at least forty thousand years, that is only yesterday. In 1788 when the locals were asked ‘what is this place?’, the answer they gave was ‘werrong’ or ‘warran’ which translates roughly as ‘here…this place’. Perhaps Sydney would be better named Warran?” Barani is an interactive, searchable resource about Sydney’s Indigenous history, from earliest pre-contact traces to most recent events.

Barani: “Barani is an Aboriginal word of the Eora, the original inhabitants of the place where Sydney City now stands. It means ‘yesterday’. Sydney dates from the arrival of the first convicts to the place in 1788. For Indigenous people, who have lived here for at least forty thousand years, that is only yesterday. In 1788 when the locals were asked ‘what is this place?’, the answer they gave was ‘werrong’ or ‘warran’ which translates roughly as ‘here…this place’. Perhaps Sydney would be better named Warran?” Barani is an interactive, searchable resource about Sydney’s Indigenous history, from earliest pre-contact traces to most recent events.

Ooodgeroo Site: Resources — Queensland University of Technology.

Ooodgeroo Site: Resources — Queensland University of Technology.

Magabala Books. For some up to date information about Aboriginal writing.

Magabala Books. For some up to date information about Aboriginal writing.

Aboriginal Art & Culture: an American eye. “A collection of personal reflections and readings on the art of the indigenous people of Australia, their culture, anthropological studies, the art market, and whatever else strays across the cultural horizon.”

Aboriginal Art & Culture: an American eye. “A collection of personal reflections and readings on the art of the indigenous people of Australia, their culture, anthropological studies, the art market, and whatever else strays across the cultural horizon.”

AusAnthrop: anthropological research, resources and documentation on the Aborigines of Australia — thanks to Jim Belshaw for this one.

AusAnthrop: anthropological research, resources and documentation on the Aborigines of Australia — thanks to Jim Belshaw for this one.

Jim Belshaw’s Personal Reflections now has some very substantial entries on Aboriginal Australia from what might be called a somewhat conservative viewpoint (in some respects) but always thoughtful and clear-sighted.

Jim Belshaw’s Personal Reflections now has some very substantial entries on Aboriginal Australia from what might be called a somewhat conservative viewpoint (in some respects) but always thoughtful and clear-sighted.

Transient Languages & Cultures came to me via Jim Belshaw in late June 2007: “This blog [from the University of Sydney Linguistics Department] covers many different projects and groups all with the common theme of endangered languages and culture.”

Transient Languages & Cultures came to me via Jim Belshaw in late June 2007: “This blog [from the University of Sydney Linguistics Department] covers many different projects and groups all with the common theme of endangered languages and culture.”

Many Nations, One People (ABC-TV) is an introduction to Aboriginal culture and society for upper primary and lower Secondary school students. Featuring contemporary documentary case studies, the series underlying theme is to present the great diversity of Aboriginal peoples and communities across Australia.

Many Nations, One People (ABC-TV) is an introduction to Aboriginal culture and society for upper primary and lower Secondary school students. Featuring contemporary documentary case studies, the series underlying theme is to present the great diversity of Aboriginal peoples and communities across Australia.

Birra News. Published by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland.

Birra News. Published by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland.

* On Wild Cat Falling: see Gary Foley on the vexed question of Mudrooroo’s aboriginality: Muddy Waters: Archie, Mudrooroo & Aboriginality. Archie Weller is another WA writer, whom I met on several occasions.

Richard Frankland is fantastic – the Circuit, SBS TV. Heard him speak at the Bris Writer’s festival. Strong and confronting speaker.

Also – MUST READ – Alexis Wright – Capricornia. Brilliant piece of literary fiction. Miles Franklin winner (of course you know that, but worth adding to your list of excellent source material.

(I used to be Uncle Bob Maza’s acting agent in Sydney – lovely man).

hughesy

October 19, 2007 at 8:32 pm

Thanks for that. Yes, I met Uncle Bob Maza in 1988.

ninglun

October 19, 2007 at 8:41 pm

Thank you for sharing this.

It’s always interesting learning about the history of indigeneous peoples. As one descended from Hawaiians, I am always disheartened to learn what was so easiliy accepted as in their best interests, was in fact, demeaning and had long lasting dire consequences.

kanani

February 19, 2008 at 2:26 pm

You’re welcome, Kanani. It is indeed pleasing to be able to report that these matters are again being addressed in a better spirit by our government.

ninglun

February 19, 2008 at 3:03 pm

thanks for these readings, they are great. If you can post special quotations that remarks their history will be great.

peace,

cecilia

March 1, 2008 at 7:39 am